“Indigenous people and individuals have the right not to be subjected to

forced assimilation or destruction of their culture.”

~ United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Article 7

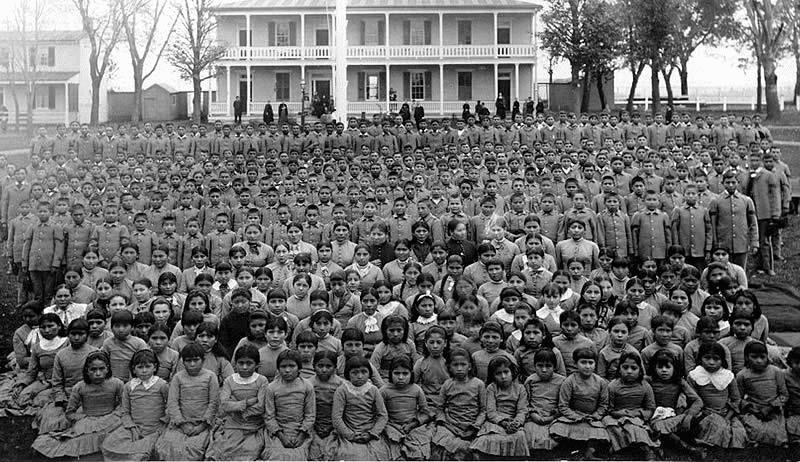

Figure 2. Native American youth at Carlisle Native Industrial School, Pennsylvania (c.1900)

Forced Assimilation and Its Impact on American Indians and Alaska Natives

Genocidal practices were used on AI/AN people well before the establishment of Indian mission and boarding schools. To help better understand the boarding school system and the role it played in a much larger agenda, it is important to first understand the definition of genocide, as well as the genocidal federal policies and experiences that preceded the boarding school system. According to the United Nations, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group such as (United Nations, n.d.):

- Killing members of the group

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group

“The impacts of genocide on AI/AN populations in the U.S. have been profound. Throughout history, AI/AN people have experienced various forms of violence, dispossession, and forced assimilation. The very experience of children who were put through boarding schools was a direct result of genocidal policy and practice. The following statement makes the level of intent clear: “Kill the Indian in him and save the man.”

− Gen. Richard H. Pratt, Superintendent, Carlisle Indian School.

A Long Legacy of Dehumanization

The dehumanization and objectification of AI/AN people was a constant feature of U.S. policy from the moment of first contact and is perpetuated to this day. Examples of this include:

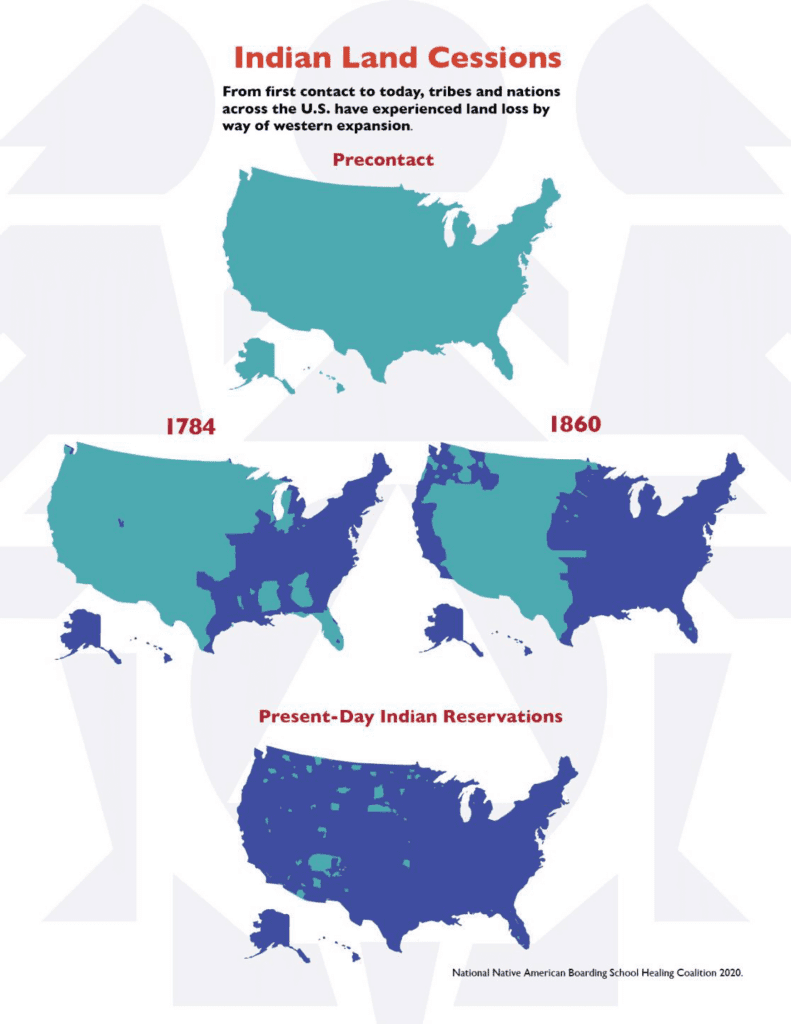

- The Doctrine of Discovery – Historical legal concepts issued by the Vatican that were used to justify the colonization of AI/AN lands, resulting in land dispossession, cultural destruction, forced assimilation, and loss of AI/AN sovereignty and rights.

- The Declaration of Independence – Authors of the Declaration of Independence referred to AI/AN people as “merciless Indian savages,” which was used as a justification for the seizure of AI/AN lands and other acts of violence (Ostler, 2020).

- The Marshall Trilogy – Three landmark Supreme Court cases that enshrined the Doctrine of Discovery into U.S. law and asserted that legal powers of landownership and sale of AI/AN lands belonged to the U.S. government.

- The Monroe Doctrine – A legal policy which declared the U.S. as sole colonizer of the Western Hemisphere.

- Manifest Destiny – An ideology that deemed White American settlers as ordained by God to pursue U.S. western expansion (Thornton, 1990).

Call To Action: Native Land

Research whose land you are on and learn about the history of the AI/AN people who live there. Native-Land.ca is a useful tool for researching these matters.

These legal concepts and policies are the bedrock of White supremacist structures and thinking. They paved the way for further dehumanization of AI/AN people in early American literature as savage animals to be killed or tamed, oversexualized objects or stereotypical villains in Western films, and caricature mascots for sports teams, all of which persist to this day. The systemic othering of AI/AN peoples has contributed to overt acts of racism and discrimination historically and currently, like the implementation of Indian boarding schools and over-representation in both foster care and the criminal legal systems today.

Call To Action: Dos and Don'ts

- Do not wear other people’s traditional clothing as a costume.

- Hold your friends and family accountable when they use problematic language about AI/ANs.

- Be an ally: Learn with humility, center the impacted, step up or stand back when asked to do so.

- Learn about the difference between cultural appreciation and appropriation:

- Do: Buy art, textiles, jewelry, music made by AI/AN people

- Do: Attend public events lead by AI/AN people

- Don’t: Buy “Native style” art, jewelry, textiles made by non-Natives

- Don’t: Attend traditional AI/AN ceremonies lead by non-Natives (or facilitate them)

Microaggressions against AI/AN people occur in almost every aspect of modern American life, including the workplace, schools, hospitals, and in popular media. The legacy of these policies has had a lasting impact on how AI/AN people are perceived not only by others but by themselves, due to loss of land, loss of culture, loss of language, and thus a loss of identity fed by internalized racism.

Call To Action: Stereotypes and Microaggressions

Avoid using stereotypes or forcing AI/AN people to endure microaggressions. Common examples of these include:

- But you don’t look Indian?

- How much Indian are you?

- What are you?

- You’re really well spoken.

- Let’s have a powwow (when referring to a meeting, discussion, etc.)

- Do you live in a tepee?

- I need to find my tribe (when referring to finding your community, or like-minded people).

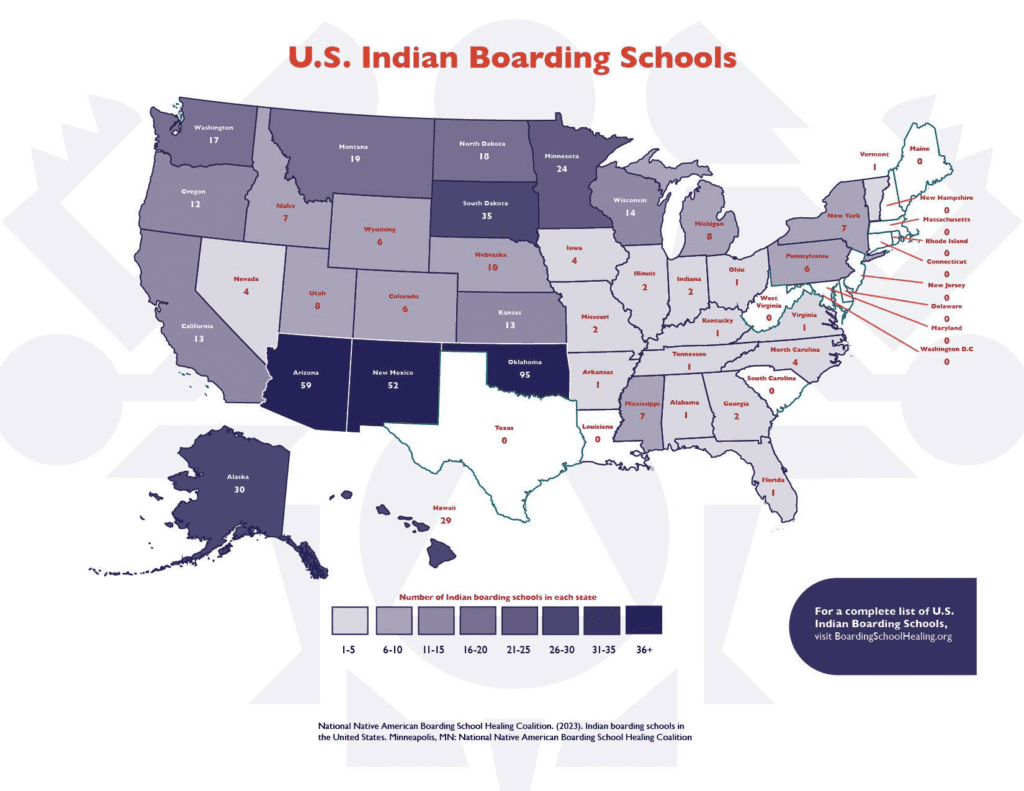

Overview of U.S. Indian Boarding Schools

Between 1819 and 1969, the U.S. Department of the Interior operated 408 Indian boarding schools (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2022). As part of a program of cultural genocide and assimilation, AI/AN children were forced to attend these schools, which replaced their languages and cultures with English, Western agriculture, and Christianity. AI/AN children were taken from their families, physically and psychologically abused, molested and sexually assaulted, and even killed. This was not a mistake. Rather, the boarding-school system was a deliberate strategic attempt to assimilate AI/AN children through consistent, insidious tactics which included the following:

- Forced removal and relocation of AI/AN children

- Renaming Indian children from Indian to English names

- Cutting the hair of Indian children, which was of great cultural significance

- Discouraging or preventing the use of AI/AN languages, and practice of AI/AN religions or cultural practices

- Organizing AI/AN children into units to perform military drills

Highlight: Tracing Your Ancestors

It is important to note that children’s experiences at Indian boarding schools were diverse and complicated. Get to know your clients, ask questions, and listen to their perspectives. Be informed about the history of AI/AN assimilation policy, be ready to learn from each person’s lived experience and seek supports when necessary. If you are interested in tracing your ancestors’ experience at Indian boading schools, The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition will be launching an online platform to help. In the meantime, please see their document “Locating Relatives at U.S. Indian Federal Boarding Schools Research Pathfinder.”

Please take a moment to make sure this is the right time to go down this path, as this work can activate a secondary trauma response. Also keep in mind that not every survivor defines their boarding school experience as adverse—AI/AN people may be at various stages of reconciliation with this experience, and it is important to respect their individual healing processes.

Through these and other policies, the boarding schools systematically replaced AI/AN people with Western military and religious systems. School officials, predominantly from religious institutions, forced foreign names, clothes, and haircuts onto students—and they divided students into mixed tribal groups without a common language. Children were punished for practicing their cultures and religions, including the crucial rites of passage from the physical world to the spirit world upon the death of a parent. The goal was not only to break cultural connections, but also to deter students from running away from the schools by depriving them of external community.

Figure 3. Students and teachers from the government Indian school on the Swinomish Reservation, Washington (c. 1907)

Physical abuse was rampant in the boarding schools. Students who spoke their Native language or otherwise resisted assimilation were flogged, whipped, slapped, cuffed, put into solitary confinement, denied food and medical attention, and more. Students were raped and sexually assaulted, often by teachers and school administrators. Poor living conditions, overcrowding, and malnutrition at the schools made infectious disease widespread. More than 500 children died at the 408 boarding schools between 1819 and 1969, with 50 schools known to have gravesites—an estimate expected to grow significantly as more evidence emerges (Levitt et al., 2023).

Indian boarding schools were also child labor mills. Students learned Western agriculture and were forced into manual labor, often growing crops and raising livestock that the schools needed. The institutions were, “in effect, envisioned as schools for civilization, in which Indians under the control of the agent would be groomed for assimilation” (Newton, 2019). Thus, in addition to social-engineering away AI/AN identity and treaty obligations, the boarding schools served a dual purpose of creating an exploitable workforce.

In 1975, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act turned over education management to tribes. By the 1980s, most large boarding schools were closed. Now, the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) operates a small number of schools, of which only four are off-reservation residential schools (Indian Boarding Schools, 2019).

Activities: Reflection Questions

Reflection Questions:

- How was the history I was taught in school similar or different than what I am learning about in this toolkit?

- Why is it important to understand this history and how it impacts the families I serve?

Digital Storytelling

Digital storytelling is a powerful tool for communicating and processing complex emotions using digital technologies. It combines narrative storytelling by way of voiceover with photography, animation, film clips, text, and audio to create a three- to five-minute-long video. Not only can digital stories be used for telling personal narratives, but they can be used to explain concepts, historical events, or make an argument.

Much of the technology needed to create a digital story is already available on cell phones and computers. To make a digital story, you will need photos, a camera, a microphone, and video editing software. Some devices have video- and audio-editing software already installed, but there are free resources available online as well.

Using one of the prompts below, write a script of roughly 200–500 words. Once you have completed your script, gather or create some visual elements to help tell your story, as well as any audio you would like included, such as background music. You will record the script you wrote as your narration or voiceover using the internal microphone on your cell phone or computer. Once you have all your visual and audio assets gathered, begin to piece the material together for your digital story with the video-editing software.

Digital Storytelling Prompts:

- For AI/AN readers:

- What are the ways you see your ancestors’ or family members’ boarding school experience impacting you or your children?

- What does healing look like for my family/clients/community?

- For non-Native readers:

- What does holding space for my clients or students look like?

- When I show up for my clients in a good way, but I am not sure what to say or do, it feels like …

Examples of digital stories:

- Barbara Aragon (Laguna Pueblo, Crow, French-Canadian), “Seal Woman”

- National Indian Council on Aging, Inc., “Cycle of Life: Native Elder Bikes to Wellness”

Further information on creating digital stories:

- Share Your Story: A How-to Guide for Digital Storytelling (SAMHSA)

- Digital Storytelling Introduction (SAMHSA)

Historical Impacts

“[My grandmother] was farmed out to a doctor’s family in Portland [Oregon] as a maid and housekeeper from the boarding school. I wonder what she wanted to be before boarding school. What were her dreams? They were all just taken from her.”

− Gary Neumann, CPS (Salish)

Early in the 19th century, the federal government recognized the importance of the Indian family unit (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2022). For nearly 500 years, breaking apart Native families was a goal of the federal Indian Policy of Assimilation. In 1928, the Secretary of the Interior reported that the policy did not assimilate Native people, but it did destroy Native families.

“This worst of its features still persists,” the report said, “and many children today have not seen their parents or brothers and sisters in years.”

The Indian boarding school system continued breaking apart families for 41 years after that report was published. The destructive effects of this program continue to influence AI/AN families today and, without adequate measures to heal intergenerational trauma, will extend to future generations.

Highlight: Grief Work

“Without griefwork—without a voice—trauma is passed from one generation to the next.” –Jane Middleton-Moz, MSCP

The federal Indian boarding school program was part of a broader system of cultural genocide toward AI/AN people. The school system separated children from family, culture, and language while a broader program of reservations and territorial dispossession removed entire tribes from the land and environment their culture was built on. Early forced-removal policies shuffled AI/AN people of distinct and different cultural identities together as an intentional effort to break down cultural identity (Dippel, 2014). Later, federal policies forced Native people away from their families and into urban areas (Walls et al., 2012).

In many AI/AN tribes, children learned about their world from their families, not from school. Kinship systems for the Cheyenne, for example, are how children learn traditional values of respect, reciprocity, and balance (Killsback, 2019). The great diversity of AI/AN people in the U.S. together hold a vast body of knowledge about the environments they have had a relationship with since time immemorial. And many of these relationships were purposely destroyed by federal programs of forced removal.

Centuries of disruption still impact the daily lives of AI/AN people in the United States. Trauma, like knowledge, is often passed on to the next generation. This builds up, and shows up, in many ways for AI/AN people today.

Click graphics to expand.